B-HIVE Structure Highlight: Tilting the cryo-EM stage

Re-orienting proteins

Researchers use cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to image vitrified macromolecules, such as ligand-bound RNA polymerase or drug-bound HIV integrase, to elucidate high-resolution information regarding the shapes of these entities. The central assumption is that the vitrified molecules will adopt several random orientations from which high-resolution information can be retrieved for a 3-D reconstruction. But, because molecules often appear in a limited number of “preferred orientations”, a complete and accurate 3-D model is often challenging to derive.

B-HIVE researchers turned, or rather tilted, the table on this problem. The researchers tested how tilting the specimen stage during cryo-EM imaging provided additional viewing angles to improve data collection. They also developed novel computational image processing approaches to obtain more accurate 3-D models of the vitrified macromolecules.

For samples embedded in vitreous ice, tilting the stage means looking through a greater thickness of ice and having increased noise in the image. The researchers hypothesized that for large macromolecules this may not be much of an issue. But for progressively smaller molecules, tilting should result in more noisy images, yielding lower resolution 3-D reconstructions. They carefully assessed how tilting the stage impacted image resolution for molecules of varying sizes to better determine the trade-offs for high-resolution information retrieval during this process.

Going full-tilt

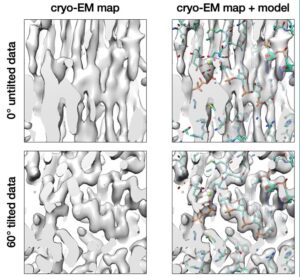

The researchers’ hypothesis was confirmed: For large macromolecules like the AAV2 capsid (3.9 MDa in size), the resolution at a 60° tilt was indistinguishable from a 0° tilt. For medium-sized molecules like apoferritin (510 kDa), virtually no loss of resolution was detected at a 60° tilt. For smaller specimens like the 230 kDa DPS protein, tilting the stage marginally decreased the resolution of the final 3-D reconstruction, but successfully overcame the issue of preferred orientation.

Most modern cryo-EM stages can tilt up to around 60°. But since small specimens lose resolution as the stage tilt angle increased, how much should a researcher tilt the stage for best results? The authors answered that question by calculating the sampling compensation factor, a measure of the effect of different particle orientations on the effective spectral signal-to-noise ratio. The authors also developed a predictive tool in which, given a predisposition towards preferred orientation, researchers can calculate the ideal tilt angle of the specimen stage to ameliorate the detrimental effects of preferred orientation. This tool helps researchers decide optimal tilt angles on-the-fly during data processing.

Additionally, the researchers imaged vitrified RNA polymerase, a gold standard specimen for pathological preferred orientation, using a maximum stage tilt angle of 60°. By imaging an RNA polymerase bound to an unnatural base, the authors found that tilting the stage allowed them to capture new details of the enzyme complex, including molecular details of how the polymerase interacts with the unnatural base. These details are difficult to decipher from data collected without any stage tilt.

What this tells us about HIV-1

Improved 3-D imaging of HIV proteins, such as integrase, which catalyzes the irreversible integration of viral DNA into the host genome, may aid in understanding drug interactions and inform researchers regarding drug resistance pathways. In cases where the site of drug interactions is inaccessible to imaging due to the preferred orientation of the protein, tilting the stage may allow for development of better models and consequently aid in making drug-protein interactions clearer.

The authors now routinely use the stage tilting methodology to overcome preferred orientation issues and develop improved reconstructions of the specimen when imaging drug-bound states of the HIV intasome. Tilting the stage provides a way to imaging multiple orientations of molecules and is a generalizable method that can benefit a wide range of specimens. Although incorporating stage tilting potentially adds some additional user input and effort during imaging, the authors advocate that the advantages substantially outweigh the quantifiable risks to retrieving uniform high-resolution information. The resulting reconstructions typically are much better sampled, the authors say, and consequently can result in better quality reconstructions for elucidating atomic details of the imaged specimen.

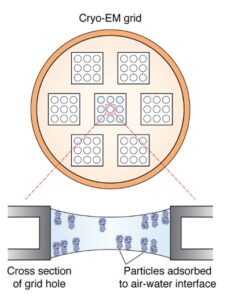

Schematic of a cryo-EM grid. Squares represent a collection of holes, and each hole has several particles embedded within vitreous ice. Cross-section view of a single hole demonstrates behavior of particles exhibiting “preferred orientation”.

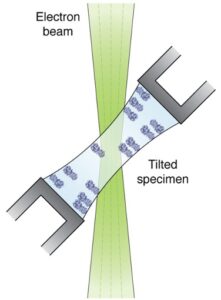

Schematic of a cryo-EM grid undergoing specimen stage tilt with respect to a unidirectional electron beam.

Example of a section of a cryo-EM reconstruction fitted to an atomic model for a tilted and an untilted dataset, with the 60° specimen stage tilted dataset showing superior map reconstruction quality.

Meet the Researcher

How did you get interested in science?

I was born and brought up and did much of my schooling in India. At the time, some of the more preferred vocations for a career were engineering or medicine or finance. My parents were encouraging me to look at alternative career options. I read a small article in the newspaper about the power of genetics and how you inherit genes. And that concept at the time was fascinating to me. So that’s what pushed me towards exploring a career in science and research.

The next big push for me was with respect to model systems. I heard a talk from an aging expert about how he uses yeast as a model system to study something as complex as aging. That spurred this interest in me that you can use different model systems to answer a lot of really interesting questions regarding human biology. So that’s what pushed me to towards applying for a Ph.D. here in the U.S. During my lab rotations, I rotated in a lab which was studying a mouse retrovirus called murine leukemia virus (MLV), which is related to HIV. And while I was doing the rotation, my subsequent mentor was saying that this model system was used for some of the very first gene therapy trials. That again was fascinating to me that viruses not only cause infections, but you could actually manipulate them for a lot of biotechnological and clinical applications. So, my thesis was trying to study how MLV actually mediates integration of viral DNA into the host genome. That was my segue into Dmitry Lyumkis’ lab, because as I was wrapping up my Ph.D., his lab came up with the very first structure of an HIV integration complex with viral DNA and target DNA.

My Ph.D. had two main components. One was structural biology using solution NMR and the other was sequencing of viral integration events using high-throughput sequencing platforms. So, for my postdoctoral work, I was wanting to either continue using a structure-based approach or a genomics-based approach. Dmitry came to give a talk at Rutgers, and after a productive chat, it set the ball rolling for me to pursue postdoctoral work in his lab. Although a lot of my focus in Dmitry’s lab has been methods development and studying other low abundance complexes, owing to my background in retroviral integration I’ve helped contribute to some of the work that the lab is doing with respect to HIV integrases and other related retroviral integrases.

Tell us about the lab where you did this work.

The lab has a very strong focus in structure-based methods, predominantly cryo-EM, for elucidating high-resolution structures of macromolecules and macromolecular complexes. We are at the Salk Institute, a premier non-profit biomedical research institution in La Jolla, CA. We perform all of our specimen preparation work at Salk and we partner with several local institutions like UCSD, Scripps Research and Sanford Burnham Prebys, and national facilities for high-resolution cryo-EM data collection.

The lab has two really strong interests. One is in methods development, the other is in the biology underlying HIV integration. But the lab has also started to branch out to understand chromatin biology in greater detail, as there is emerging evidence that these two processes – retroviral integration and gene expression regulation – are closely linked, albeit through complex mechanisms that we still poorly understand.

What were the biggest challenges with this study?

A lot of people have a bias against tilting the specimen stage when collecting data, because more user input may be needed. For RNA polymerase, our biologically relevant test case, the data collection actually did require a lot of user intervention. Because as you tilt the stage more, you have to adjust the concentration of your protein complex that you actually apply on the specimen holder to prevent particles from overlapping during tilting. At lower concentrations, however, the interfacial effect that forms a film of buffer with embedded protein complexes has unexpected characteristics, resulting in several holes being empty without any imageable protein complexes. This was something that I wasn’t expecting and ended up posing a lot of challenges for automated data collection. Since more than ninety percent of images were not imageable, using whatever experience I had built over past several years, I had to visually ascertain what might be good areas to collect. Although this could be done using the data collection software, owing to the dramatic stage tilt angles, it is still not good enough for us to accurately pick out regions of interest. This resulted in me using an unorthodox approach of manually picking locations that normally folks don’t consider during automated data collection.

Nevertheless, we still went ahead with my data collection scheme and this resulted in really conclusive data reinforcing the power of specimen stage tilt for overcoming the preferred orientation issue. In addition to RNA polymerase, we collected close to thirty different data sets for this study, which is way more than what you normally see in standard publications. But this aspect of the work was not as challenging, since with good organization and planning we could get enough data to address all of our questions that we had with respect to how tilting affects resolution and how much it benefits in overcoming preferred orientation?

What are you working on now?

The next biggest thing is: Can we now make this more user-friendly? The most obvious direction to take is whether we can make stage-tilting more automation friendly. To this effect, we are figuring out if we can develop tools that can be embedded into standard data collection or data processing software where there is minimal user intervention needed to identify optimal stage tilt-angles, and you can still collect data sets that yield high-quality maps in terms of both isotropy and resolution.

I think most of the people that want to use the technology don’t want to spend their time trying to develop methods. They’re more interested in using cryo-EM for addressing biological questions. Hopefully, our tools will push more labs to adopt specimen stage tilt as a strategy for obtaining high-quality cryo-EM maps. The other alternative, in the absence of wanting to tilt the stage, is doing extensive screens for additives and detergents. Since stage tilting is much simpler, the only question is by how much to tilt and how best to make good grids for a given tilted data collection experiment.

We have developed a tool precisely for this purpose and it is available on GitHub for folks to determine the optimal stage tilt angle. You don’t have to take out a protractor and measure the tilt of the stage! It does calculations to tell you how much you would need to tilt the stage to overcome the preferred orientation. We are currently working on improving this tool and embedding it into popular software platforms.