B-HIVE Research Highlight: Investigating latency and viral reservoirs

Epigenetic regulation of latency

One of the most significant barriers to eliminating HIV-1 in hosts is the virus’ integration into the host genome, creating reservoirs of dormant virus in the body that have the potential to reactivate after therapy interruption. While many researchers are working on developing and refining “functional cures,” or treatments that can control HIV-1 replication without the need for continued treatment, achieving full eradication of HIV-1 requires disrupting latent reservoirs.

At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the lab led by B-HIVE Collaborative Development Program grantee Guochun Jiang is studying HIV-1 latency using multiple models. These include cell and tissue models, HIV-infected humanized mice, SIV-infected nonhuman primates, and people with HIV on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Jiang’s lab studies epigenetic regulation of HIV-1 latency. One of the lab’s recent findings is that a significant epigenetic regulator of latent HIV is histone crotonylation. Crotonylation shares some similarities to histone acetylation, but appears to serve a distinct purpose in HIV transcription.

Characterizing HIV reservoirs

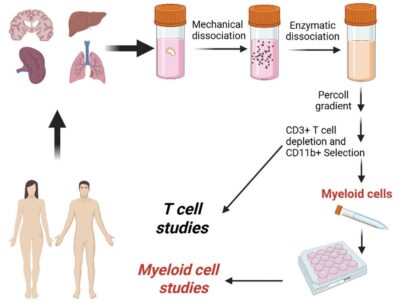

Although T cells are commonly associated with HIV-1 infection, non-T cells, particularly brain microglial cells, can also serve as a reservoir for latent HIV-1. The Jiang lab studies and characterizes HIV-1 reservoirs, particularly brain cells including myeloid cells and astrocytes. Supported by the B-HIVE Collaborative Development Program, Jiang and his lab studied non-T cell reservoirs, finding that epigenetic regulation played a significant role in maintaining reservoirs in microglia. The lab has already secured multiple R01 awards, including collaborative grants with partner institutions, to continue studying this reservoir.

How this lab is advancing HIV research

HIV-1 reservoirs in the central nervous system present unique challenges. Traditional eradication strategies may not work, since even a brief reversal of latency in brain cells could lead to neuroinflammation and damage to neuronal cells. The Jiang lab is exploring approaches that could silence HIV-1 in the central nervous system. Studies using microglia from nonhuman primates and people with HIV-1 suggest that an approach toward a functional cure, rather than full eradication, in brain HIV reservoirs may be effective and achievable.

The lab is also looking to target the epigenetic regulators of HIV-1 reservoirs. Jiang lab researchers recently identified a small molecule that selectively disrupts histone crotonylation, targeting latent HIV-1 while leaving other epigenetic processes unaffected. This approach could be used in concert with other therapeutic strategies in eradication efforts.

An illustration depicting the process of studying T-cell and non-T-cell HIV reservoirs.

Meet the Researcher

How did you get interested in science?

I grew up in a rural county in China. During my childhood, the country was just beginning to recover from the so-called “Ten Years of Catastrophe”—the devastating Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976, during which the economy, education, and science were pushed to the brink of collapse. At that time, many children were encouraged to pursue STEM fields for their future careers. I was fortunate to be part of the new generation that eagerly embraced science during this critical period of national recovery. Around then, there was a growing belief that the 21st century would be a golden era for modern biology. So, when I had to choose a college major, my first choice was Biochemistry. However, for various reasons, I was placed in the Microbiology program instead. That marked the true beginning of my education and scientific career in microbiology—starting with bacteria, then fungi, and eventually viruses, which remain my focus today.

Tell us about the lab where you did this work.

My laboratory is based at the UNC HIV Cure Center and the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The team currently includes four postdoctoral fellows, two Ph.D. students, one master’s student, and two research technicians. In addition, we actively train many undergraduate students each year, both during the academic year and over the summer. Our work is highly collaborative by necessity. Much of our research focuses on tissue-resident immune cells, which must be carefully isolated from necropsies of humanized mice, nonhuman primates, and from rapid research autopsies of people with HIV enrolled in the “Last Gift” Program at the University of California, San Diego. Tissue processing, isolation, and maintenance of these cells are extremely time-consuming and technically demanding, requiring close coordination and teamwork within the lab. Beyond our own studies, and with NIH support, we also provide these rare and hard-to-obtain freshly isolated tissue-resident cells to collaborators across the country. This resource enables other investigators to test their scientific hypotheses and strengthen their NIH grant applications, thereby amplifying the broader impact of our work.

What were the biggest challenges with this study?

One of the greatest challenges remains accessing rare tissue-resident immune cells, particularly brain myeloid cells such as microglia. These cells are extremely difficult to obtain, yet they are essential for advancing our understanding of HIV persistence in the central nervous system. The Jiang Lab works diligently to provide not only for its own research but also to support many other laboratories by sharing these hard-to-obtain cells for their studies and NIH grant applications. We are at a critical juncture in HIV cure research. After more than 30 years of continuous effort, the scientific community is closer than ever to achieving a potential cure. However, this progress relies on uninterrupted support—from funding agencies, institutions, trainees, and laboratory staff. Any disruption in this support, even for a short period, could have profound consequences for biomedical research and the 38 million people living with HIV in the United States and around the world. Sustained commitment is therefore essential to ensure that this momentum is not lost.

What are you working on now?

In light of these challenges, my laboratory continues to investigate the basic science of persistent HIV infection, with a particular focus on how histone crotonylation regulates HIV transcription and latency. Although histone crotonylation shares the same enzymes as histone acetylation and many other acylation modifications, our recent data suggest that it plays a distinct regulatory role in HIV transcription and latency. We are now identifying and characterizing selective crotonylation-targeting compounds, which will allow us to dissect the unique structural and biochemical mechanisms underlying this epigenetic selectivity. In parallel, we are investigating why immune activation, including neuroinflammation, persists in people with HIV despite long-term successful antiretroviral therapy. Our ongoing work has begun to uncover the triggers of this persistent immune activation, and we believe that these pathways could be targeted to curtail chronic inflammation, thereby improving mental health outcomes for people with HIV.